National Register of Historic Places

The National Register is the nation's list of cultural resources with significant histories. The National Park Service maintains the list. It includes buildings, archaeological sites, and neighborhoods that are important to history. There are many districts and individual properties in Madison on the National Register. This is separate from local historic designations by the Madison Landmarks Commission. The commission does not regulate the National Register program.

The National Register is an honorary designation that comes with some financial incentives. There are two tax credit programs. One program is for rehabilitation of income-producing properties. The other is for the rehabilitation of single family homes. Visit the Wisconsin State Historical Society for more information about tax credits.

Below are maps of districts, or you can explore an interactive map

____________________________________________________________________________________

East Dayton Street

This district includes three buildings at East Dayton Street and North Blount Street. The buildings are remnants of Madison's first African-American neighborhood. All three were moved here from elsewhere in the City. Before the Civil War, few African-American families lived in Madison. Those who did rented housing and most of their histories were never recorded. By 1900, there were nineteen African-American households in the City. Three families owned their own homes. This included John and Martha Turner who came to Madison from Kentucky in 1898. The Turners created the Douglass Beneficial Society, a self-help group for African-American families. They moved a building to 649 East Dayton Street to house the activities of the Society. The Turners were also instrumental in organizing the first African-American church in Madison. Around 1903, the group moved a former Norwegian Lutheran church to 631 East Dayton Street. It is no longer in existence. The society and the church encouraged other African-American families to move to there. In 1910, three of the six homeowners in Madison lived near the corner of Dayton and Blount. Nineteen of the thirty-nine African-American households were in this area.

This district includes three buildings at East Dayton Street and North Blount Street. The buildings are remnants of Madison's first African-American neighborhood. All three were moved here from elsewhere in the City. Before the Civil War, few African-American families lived in Madison. Those who did rented housing and most of their histories were never recorded. By 1900, there were nineteen African-American households in the City. Three families owned their own homes. This included John and Martha Turner who came to Madison from Kentucky in 1898. The Turners created the Douglass Beneficial Society, a self-help group for African-American families. They moved a building to 649 East Dayton Street to house the activities of the Society. The Turners were also instrumental in organizing the first African-American church in Madison. Around 1903, the group moved a former Norwegian Lutheran church to 631 East Dayton Street. It is no longer in existence. The society and the church encouraged other African-American families to move to there. In 1910, three of the six homeowners in Madison lived near the corner of Dayton and Blount. Nineteen of the thirty-nine African-American households were in this area.

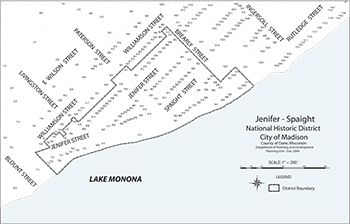

East Wilson Street

In the 19th-century railroads were crucial to economic development. Farmers, manufacturers, and other producers depended on the railroads to move their products. Railroads were also the main form of travel and migration. Commerce benefited from train traffic by grouping businesses where travelers would disembark. Around 1870 the Chicago and Northwestern Railway, and the Milwaukee Road railway, built depots here. Three rail extensions to other areas of the State passed through these depots. Businesses sprang up along Wilson Street to serve railroad passengers, employees, and vendors. A Prussian named Herman Kleuter was one of the first business owners to profit from the traffic. He opened a grocery store in 1867 on the 500 block of Wilson Street. In 1871 he built a two-story brick building at 506-508 East Wilson Street. Other entrepreneurs built hotels and commercial buildings. Merchants opened saloons, restaurants, grocery stores, tobacco shops, and barber shops. After World War II, rail traffic declined, and with it, the Wilson Street commercial area. The last Milwaukee Road passenger train left Madison in 1971.

In the 19th-century railroads were crucial to economic development. Farmers, manufacturers, and other producers depended on the railroads to move their products. Railroads were also the main form of travel and migration. Commerce benefited from train traffic by grouping businesses where travelers would disembark. Around 1870 the Chicago and Northwestern Railway, and the Milwaukee Road railway, built depots here. Three rail extensions to other areas of the State passed through these depots. Businesses sprang up along Wilson Street to serve railroad passengers, employees, and vendors. A Prussian named Herman Kleuter was one of the first business owners to profit from the traffic. He opened a grocery store in 1867 on the 500 block of Wilson Street. In 1871 he built a two-story brick building at 506-508 East Wilson Street. Other entrepreneurs built hotels and commercial buildings. Merchants opened saloons, restaurants, grocery stores, tobacco shops, and barber shops. After World War II, rail traffic declined, and with it, the Wilson Street commercial area. The last Milwaukee Road passenger train left Madison in 1971.

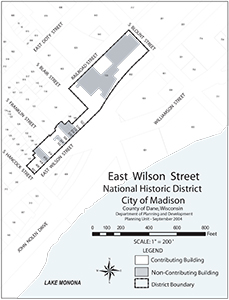

Fourth Lake Ridge

European Settlers referred to the four lakes here as First, Second, Third, and Fourth. Glaciers created the lakes and the ridge-like drumlins along the shores. The area known as the Fourth Lake Ridge runs along Lake Mendota from James Madison Park to Giddings Park. The district runs between the two parks, and from Lake Mendota to the lot lines on the south side of Gorham Street. In the early 1850s settlers began populating the area. In 1857 the Leitch House was built at 752 East Gorham Street. This is one of the finest examples of residential Gothic Revival in Wisconsin. At the time, residents felt the ridge was too far from downtown, which around the Capitol Square. In the 1890s, industry attracted more people to Madison. A streetcar three blocks from the ridge encouraged settlement in the sparse neighborhood. By 1900 most lots were occupied. Subdivision of these lots after 1900 increased the density of the neighborhood. This resulted in the construction of many houses in early 20th-century styles. The area retains its pre-World War II appearance despite change that has altered the rest of the City. It includes some of the City's best examples of early 20th-century styles. This includes Italianate, Queen Anne, Shingle, Bungalow, American Four square, Craftsman, and Prairie. It also has designs by some of Madison's master architects: Claude and Starck, Cora Tuttle, Henry T. Dysland, and Frank Riley.

European Settlers referred to the four lakes here as First, Second, Third, and Fourth. Glaciers created the lakes and the ridge-like drumlins along the shores. The area known as the Fourth Lake Ridge runs along Lake Mendota from James Madison Park to Giddings Park. The district runs between the two parks, and from Lake Mendota to the lot lines on the south side of Gorham Street. In the early 1850s settlers began populating the area. In 1857 the Leitch House was built at 752 East Gorham Street. This is one of the finest examples of residential Gothic Revival in Wisconsin. At the time, residents felt the ridge was too far from downtown, which around the Capitol Square. In the 1890s, industry attracted more people to Madison. A streetcar three blocks from the ridge encouraged settlement in the sparse neighborhood. By 1900 most lots were occupied. Subdivision of these lots after 1900 increased the density of the neighborhood. This resulted in the construction of many houses in early 20th-century styles. The area retains its pre-World War II appearance despite change that has altered the rest of the City. It includes some of the City's best examples of early 20th-century styles. This includes Italianate, Queen Anne, Shingle, Bungalow, American Four square, Craftsman, and Prairie. It also has designs by some of Madison's master architects: Claude and Starck, Cora Tuttle, Henry T. Dysland, and Frank Riley.

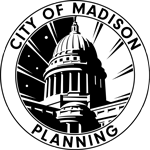

The Jenifer-Spaight district consists of a historic residential area three-block-long by two-and-a-half-blocks-wide. The triangular stretch of land is in the middle of the Third Lake Ridge local historic district. This district includes houses built from the pioneer era through the Great Depression. In the early years of Madison, the western part of the district saw a lot of residential construction. Examples of this early time that remain include:

- Hyer's Hotel, built in 1854 (854 Jenifer Street)

- The Sauthoff house of 1857 (737-739 Jenifer Street)

- The Shipley house of 1854 (946 Spaight Street)

At the turn-of-the-century, empty lots filled with houses in the popular styles of the time. This includes Queen Anne, Craftsman, Prairie, and Four-Square. The history of the district is the same as the history of the larger Third Lake Ridge historic district. This area, along with the Orton Park district, have more rehabilitated houses. For this reason these areas were listed in the National Register. Other sections of the local district may become eligible for the National Register.

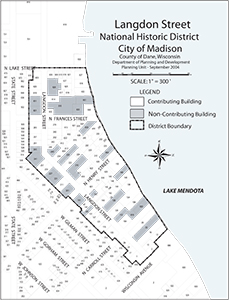

Langdon Street

The Langdon Street historic district is a rich tapestry of architecture and history. It was first a spacious neighborhood for Madison's most prominent 19th-century families. In the 20th-century it evolved into the university student enclave it is today. The buildings reflect the changes as it grew and developed over the last 150 years. In 1986, the Langdon Street historic district was listed in the National Register. This is a recognition of the historical and architectural resources in this neighborhood.

The Langdon Street historic district is a rich tapestry of architecture and history. It was first a spacious neighborhood for Madison's most prominent 19th-century families. In the 20th-century it evolved into the university student enclave it is today. The buildings reflect the changes as it grew and developed over the last 150 years. In 1986, the Langdon Street historic district was listed in the National Register. This is a recognition of the historical and architectural resources in this neighborhood.

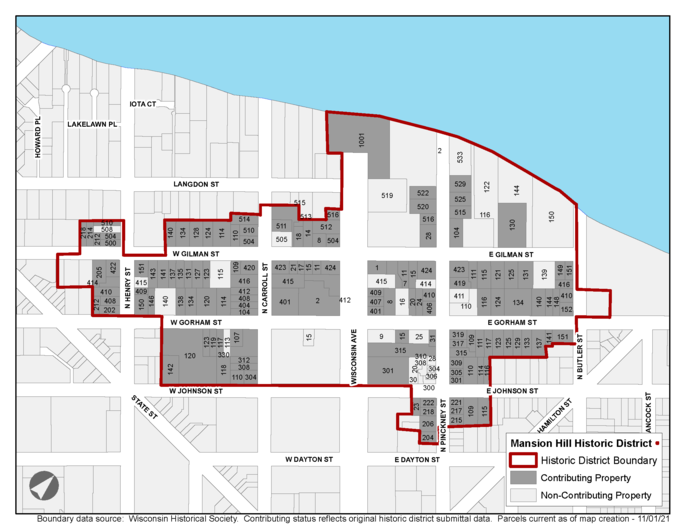

Mansion Hill

Mansion Hill is a residential neighborhood north of the Capitol Square. In the 19th-century it was one of Madison's most prestigious neighborhoods. The area was home to many influential residents. Today, it contains the largest number of intact Victorian houses in Madison. Developers in the 1950s-70s demolished houses to build apartments or commercial buildings. Concerned about more demolition, residents asked the City to create a historic district. The Common Council named Mansion Hill our first historic district in 1976.

Mansion Hill is a residential neighborhood north of the Capitol Square. In the 19th-century it was one of Madison's most prestigious neighborhoods. The area was home to many influential residents. Today, it contains the largest number of intact Victorian houses in Madison. Developers in the 1950s-70s demolished houses to build apartments or commercial buildings. Concerned about more demolition, residents asked the City to create a historic district. The Common Council named Mansion Hill our first historic district in 1976.

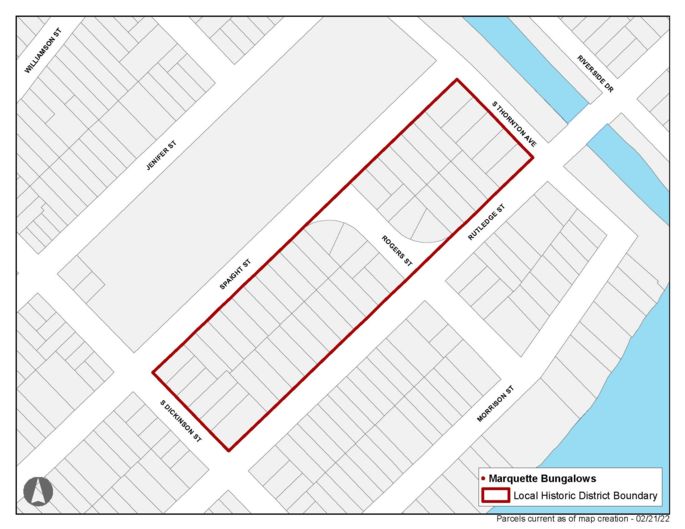

Marquette Bungalows

Marquette Bungalows is a grouping of bungalow houses on two blocks. It is bound by Spaight Street, Rutledge Street, S. Dickinson Street, and S. Thornton Avenue. In 1924 the Karrels Realty and Building Development Company planned the blocks. They named it the Soelch's Subdivision. They built five homes on the lots the first year, and continued to build several each year until 1930. In all they constructed 47 houses. The bungalows are similar in size and shape, but each has unique details. Although the houses are not large, the quality of construction is high. Many of the houses had wood floors, built-in cabinets and leaded glass windows. Common Council named Marquette Bungalows our fourth historic district in 1993.

Marquette Bungalows is a grouping of bungalow houses on two blocks. It is bound by Spaight Street, Rutledge Street, S. Dickinson Street, and S. Thornton Avenue. In 1924 the Karrels Realty and Building Development Company planned the blocks. They named it the Soelch's Subdivision. They built five homes on the lots the first year, and continued to build several each year until 1930. In all they constructed 47 houses. The bungalows are similar in size and shape, but each has unique details. Although the houses are not large, the quality of construction is high. Many of the houses had wood floors, built-in cabinets and leaded glass windows. Common Council named Marquette Bungalows our fourth historic district in 1993.

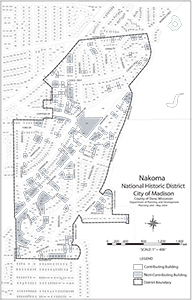

Nakoma

Around 1890, Madison experienced major population growth. This was a result of the growth of the University of Wisconsin, the state government and the industrial sector. The increased density affected the traditional quality of life in the downtown area. Houses were squeezed between older homes, and new apartment buildings were built. This resulted in an exodus of families seeking a better life in the suburbs.

Around 1890, Madison experienced major population growth. This was a result of the growth of the University of Wisconsin, the state government and the industrial sector. The increased density affected the traditional quality of life in the downtown area. Houses were squeezed between older homes, and new apartment buildings were built. This resulted in an exodus of families seeking a better life in the suburbs.

The Nakoma Neighborhood was the first to stretch beyond the reach of streetcar lines. As the automobile became more accessible, developers looked further for land. Platted by the Madison Realty Company in 1915, it took five years for sales of lots to take off. During this time restrictions and amenities were put in place to create an appealing area for families. Saloons, businesses, and multi-family homes were forbidden. Lot setbacks and height restrictions were implemented. All building plans required a review by a licensed architect. A private bus line was created to shuttle residents from Nakoma ever downtown and a new school was built.

By the mid-1920's new houses were appearing on every street of the original plat. Several blocks were divided to increase the number of available lots. Construction continued unabated until the onset of the Great Depression. In 1931 Nakoma was annexed into the City of Madison. By 1936 construction resumed at a pace even greater than before. By 1945 nearly all lots in the pre-WW II portions of Nakoma were occupied.

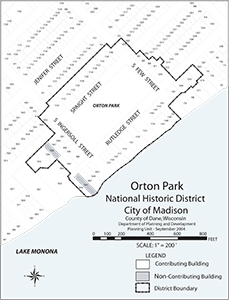

Orton Park

Orton Park was Madison's first official burying ground. After Madison became a village in 1846, trustees purchased the block to serve as a cemetery. The City was slowly growing at the time and they felt 256 plots would meet the Village's needs. After population growth and a series of cholera epidemics, we needed a larger space. Officials had the graves moved from this site to an area west of the Village. The original cemetery turned into a City park, which opened in 1887. This was an attractive new place for residential houses. The most intensive development occurred from the 1890s to the Depression. By the early 1930s all lots surrounding the park were filled. The district includes the park, houses facing it, and houses on Spaight and Rutledge. Since most houses were built between 1890 and 1920, early 20th-century styles predominate. About one-third of the houses in the district are Queen Anne. Another third are progressive Craftsman and Prairie style. The park still serves as an attractive green space, and the focal point of the neighborhood.

Orton Park was Madison's first official burying ground. After Madison became a village in 1846, trustees purchased the block to serve as a cemetery. The City was slowly growing at the time and they felt 256 plots would meet the Village's needs. After population growth and a series of cholera epidemics, we needed a larger space. Officials had the graves moved from this site to an area west of the Village. The original cemetery turned into a City park, which opened in 1887. This was an attractive new place for residential houses. The most intensive development occurred from the 1890s to the Depression. By the early 1930s all lots surrounding the park were filled. The district includes the park, houses facing it, and houses on Spaight and Rutledge. Since most houses were built between 1890 and 1920, early 20th-century styles predominate. About one-third of the houses in the district are Queen Anne. Another third are progressive Craftsman and Prairie style. The park still serves as an attractive green space, and the focal point of the neighborhood.

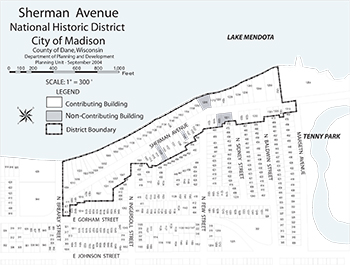

Sherman Avenue

Sherman Avenue and the surrounding area were in the original 1836 Madison plat. Sherman follows the shoreline of Lake Mendota. At the time, it was one of only a few streets that did not conform to the plat's grid. Sherman was a scenic area and was at times under water until the early 1890s. At that time the City experienced rapid growth and the first suburbs developed. Filling of low lying land in the Sherman Avenue area then became worth the cost. The district includes both sides of five-blocks from Giddings Park to Tenney Park. Streetcars made the ten-to twelve-block commute to downtown more tolerable. Nearly all houses in the district were single-family homes for the middle-class. Since most houses were built between 1890 and 1920, early 20th-century styles predominate. Of the 80 houses in the district, about a third are Queen Anne or Shingle styles. Another third are Craftsman or Prairie, and the rest are period revival. This district has many homes designed by some of Madison's most important architects. This includes Claude and Starck, Alvan Small, Gordon and Paunack, Law, Law and Potter and Frank Riley. Most houses in the district look like they did when they were built. Similar setbacks, heights, rooflines, and materials create a unified appearance throughout the neighborhood.

Sherman Avenue and the surrounding area were in the original 1836 Madison plat. Sherman follows the shoreline of Lake Mendota. At the time, it was one of only a few streets that did not conform to the plat's grid. Sherman was a scenic area and was at times under water until the early 1890s. At that time the City experienced rapid growth and the first suburbs developed. Filling of low lying land in the Sherman Avenue area then became worth the cost. The district includes both sides of five-blocks from Giddings Park to Tenney Park. Streetcars made the ten-to twelve-block commute to downtown more tolerable. Nearly all houses in the district were single-family homes for the middle-class. Since most houses were built between 1890 and 1920, early 20th-century styles predominate. Of the 80 houses in the district, about a third are Queen Anne or Shingle styles. Another third are Craftsman or Prairie, and the rest are period revival. This district has many homes designed by some of Madison's most important architects. This includes Claude and Starck, Alvan Small, Gordon and Paunack, Law, Law and Potter and Frank Riley. Most houses in the district look like they did when they were built. Similar setbacks, heights, rooflines, and materials create a unified appearance throughout the neighborhood.

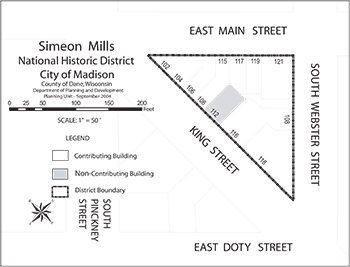

Simeon Mills

The Simeon Mills historic district is at the corner of Main and King Streets, just off the Capitol Square. The triangle-shaped block includes seven buildings, now divided into nine ownership lots. The buildings are unified by scale and materials, and are joined by party walls. The buildings were built between 1845 and 1887. Five are Italianate and one is Romanesque. Built in 1845, the Argus building (East Main at South Webster) is the oldest commercial building in Madison. As almost the entire block remains, this district shows the scale and character of 19th-century downtown.

The Simeon Mills historic district is at the corner of Main and King Streets, just off the Capitol Square. The triangle-shaped block includes seven buildings, now divided into nine ownership lots. The buildings are unified by scale and materials, and are joined by party walls. The buildings were built between 1845 and 1887. Five are Italianate and one is Romanesque. Built in 1845, the Argus building (East Main at South Webster) is the oldest commercial building in Madison. As almost the entire block remains, this district shows the scale and character of 19th-century downtown.

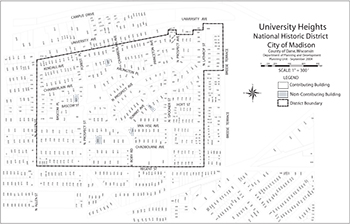

University Heights

University Heights was laid out in 1893. Its curved streets and beautiful vistas attracted families of professors and business people. The area includes some of Madison's most significant Queen Anne, prairie style and period revival houses. Madison's best architects, as well as nationally-known Keck and Keck, George W. Maher, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, designed residences in the Heights. Common Council named University Heights our third historic district in 1985.

University Heights was laid out in 1893. Its curved streets and beautiful vistas attracted families of professors and business people. The area includes some of Madison's most significant Queen Anne, prairie style and period revival houses. Madison's best architects, as well as nationally-known Keck and Keck, George W. Maher, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, designed residences in the Heights. Common Council named University Heights our third historic district in 1985.

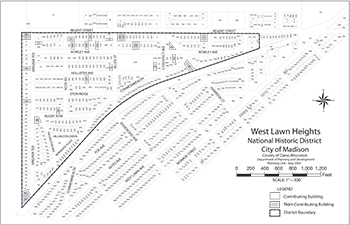

West Lawn Heights

This district was platted in three phases between 1903 and 1917 on open farmland. The wedge-shaped district comprises twenty-three City blocks. It includes nearly 400 single-family homes, two commercial buildings, and two church-school complexes. Most were built between 1906 and 1946. Leonard H. Smith, professor of civil engineering and city planning at the University of Wisconsin, designed all three plats. The developers established rules and restrictions to guarantee physical and social attractiveness. The houses are good examples of popular architectural styles from 1906 and 1946. Those built before World War I include Craftsman, Arts & Crafts, American Four square, Bungalow, and Prairie. Houses built after are almost all examples Tudor Revival or Colonial Revival. Together, the buildings show the evolution of styles in the City during that time. Most houses also have a high degree of historic integrity.

This district was platted in three phases between 1903 and 1917 on open farmland. The wedge-shaped district comprises twenty-three City blocks. It includes nearly 400 single-family homes, two commercial buildings, and two church-school complexes. Most were built between 1906 and 1946. Leonard H. Smith, professor of civil engineering and city planning at the University of Wisconsin, designed all three plats. The developers established rules and restrictions to guarantee physical and social attractiveness. The houses are good examples of popular architectural styles from 1906 and 1946. Those built before World War I include Craftsman, Arts & Crafts, American Four square, Bungalow, and Prairie. Houses built after are almost all examples Tudor Revival or Colonial Revival. Together, the buildings show the evolution of styles in the City during that time. Most houses also have a high degree of historic integrity.

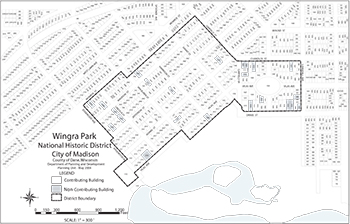

Wingra Park

Designed in 1889, Wingra Park was the first suburb to allow residents to escape the crowds on the Isthmus. The 106 acre farm was an open, well-drained property that adjoined the western edge of the city. Sales of the lots were slow at first, stalled by a slow national economy and lack of street car service. The Wingra Park Advancement Association was formed in 1893 "to beautify and improve" Wingra Park. One of their first acts was to build a neighborhood center to host activities. By 1895 electric street lights were installed. In 1897 the street car line extended down Breese Terrace to Monroe Street and then to Forest Hills cemetery. This act helped secure the success of the neighborhood. By 1903 the area was considered one of Madison's finest residential districts. The area contains some of Madison's finest Queen Anne, Prairie style and period revival homes. These buildings constitute one of Madison's most important and intact architectural legacies.

Designed in 1889, Wingra Park was the first suburb to allow residents to escape the crowds on the Isthmus. The 106 acre farm was an open, well-drained property that adjoined the western edge of the city. Sales of the lots were slow at first, stalled by a slow national economy and lack of street car service. The Wingra Park Advancement Association was formed in 1893 "to beautify and improve" Wingra Park. One of their first acts was to build a neighborhood center to host activities. By 1895 electric street lights were installed. In 1897 the street car line extended down Breese Terrace to Monroe Street and then to Forest Hills cemetery. This act helped secure the success of the neighborhood. By 1903 the area was considered one of Madison's finest residential districts. The area contains some of Madison's finest Queen Anne, Prairie style and period revival homes. These buildings constitute one of Madison's most important and intact architectural legacies.